By Michael Bitzer

One of the interesting things I found in the generic ballot questions in last month’s Catawba-YouGov Survey was a consistency of voter intentions across the five contests asked (U.S. Senate, U.S. House, N.C. Supreme Court, N.C. State House, and N.C. State Senate).

As noted in the release, Democratic candidates generally received about 45 percent of the vote to Republicans receiving 38 percent, with less than 15 percent undecided.

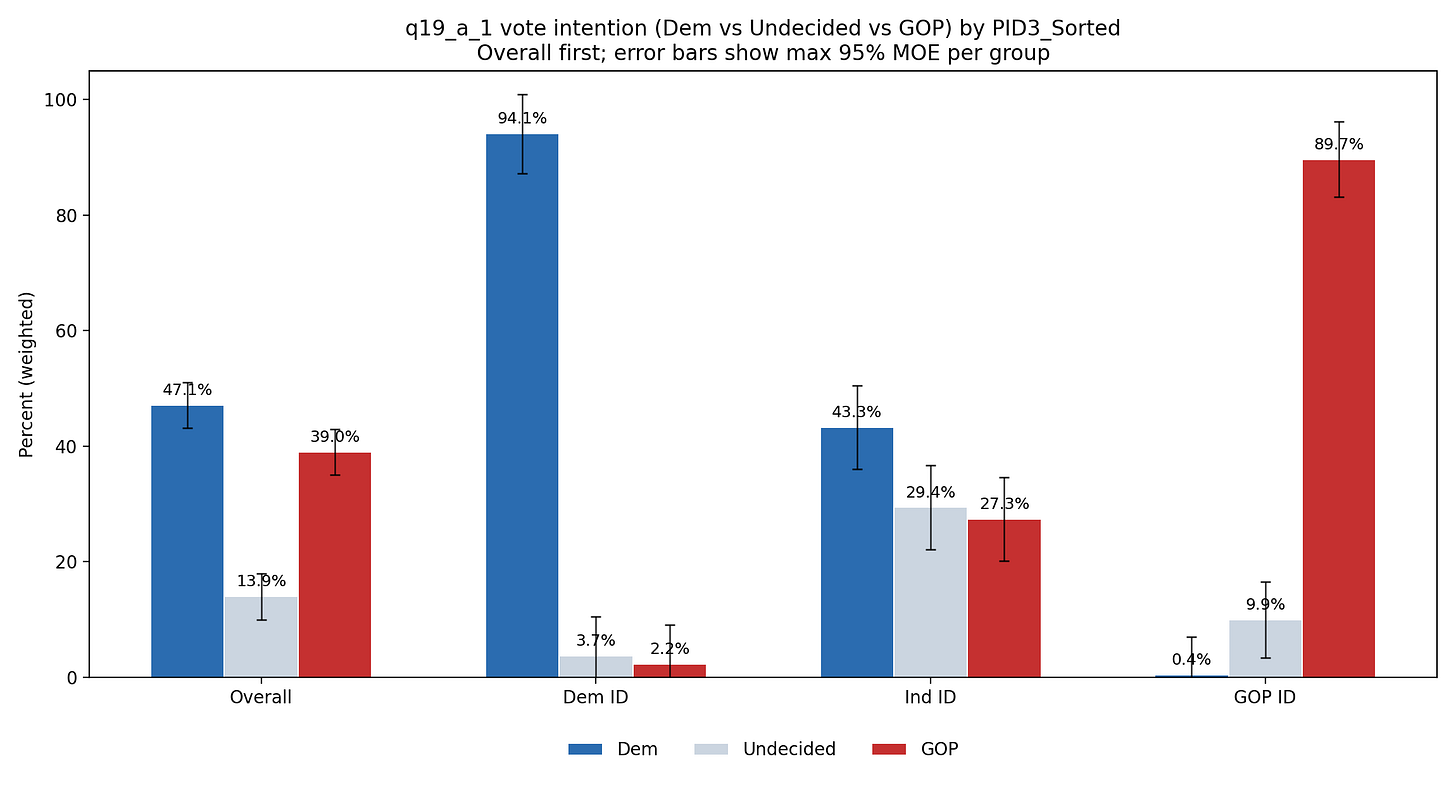

But when looking at the partisan identification, we see some distinctiveness when it comes to voter intention. Take for example the U.S. Senate generic ballot contest (broken into “definitely/likely voting for Democratic candidate vs. undecided vs. definitely/likely voting for Republican candidate”1): we see clear partisan loyalty among those who self-identify as Democratic and Republican, while those who said they were ‘independent’ are more divided, but lean towards one party.

The partisan divide jumps out with this classification, based on 94 percent of Democrats and nearly 90 percent of Republicans firmly for their party’s candidate (no matter who it is, ten-months out from November). In other words, partisan identifiers appear firmly aligned, with a small pockets of undecided voters and an even smaller share willing to cross party lines at this stage.

However, independents is where we see the political hinge. Independents aren’t “in the middle” because they’re evenly split—they’re in the middle because they’re much less settled. Nearly 3 in 10 are undecided, with the remainder Democratic-leaning at this point.

While partisans are mostly sorted in their candidate camp ten months out, initial Independents are where uncertainty concentrates: they are still choosing (or perhaps not choosing).

Once the March primary picks each party’s nominee, the general election strategy seems to be the standard two-fold for North Carolina: for partisans, partisan persuasion is likely limited, focusing instead on enthusiasm to translate into turnout. Conversely, initial independents are the electorate’s decision zone—less committed, more undecided, and not necessarily behaving like partisans at this stage.

What happens when ‘Independents’ go into a partisan camp?

In survey research, independents aren’t all the same: some lean to a party, while others truly do not. That distinction matters.

For many, the initial partisan identification hides a key dynamic at play. Once they identify as an initial independent, respondents are asked if they lean to one party or the other. In this survey, over half of the initial independents split between the two parties: 30 percent leaned Democratic and 27 percent leaned Republican. The remainder—40 percent—didn’t identify with a party, making them ‘pure independents.’

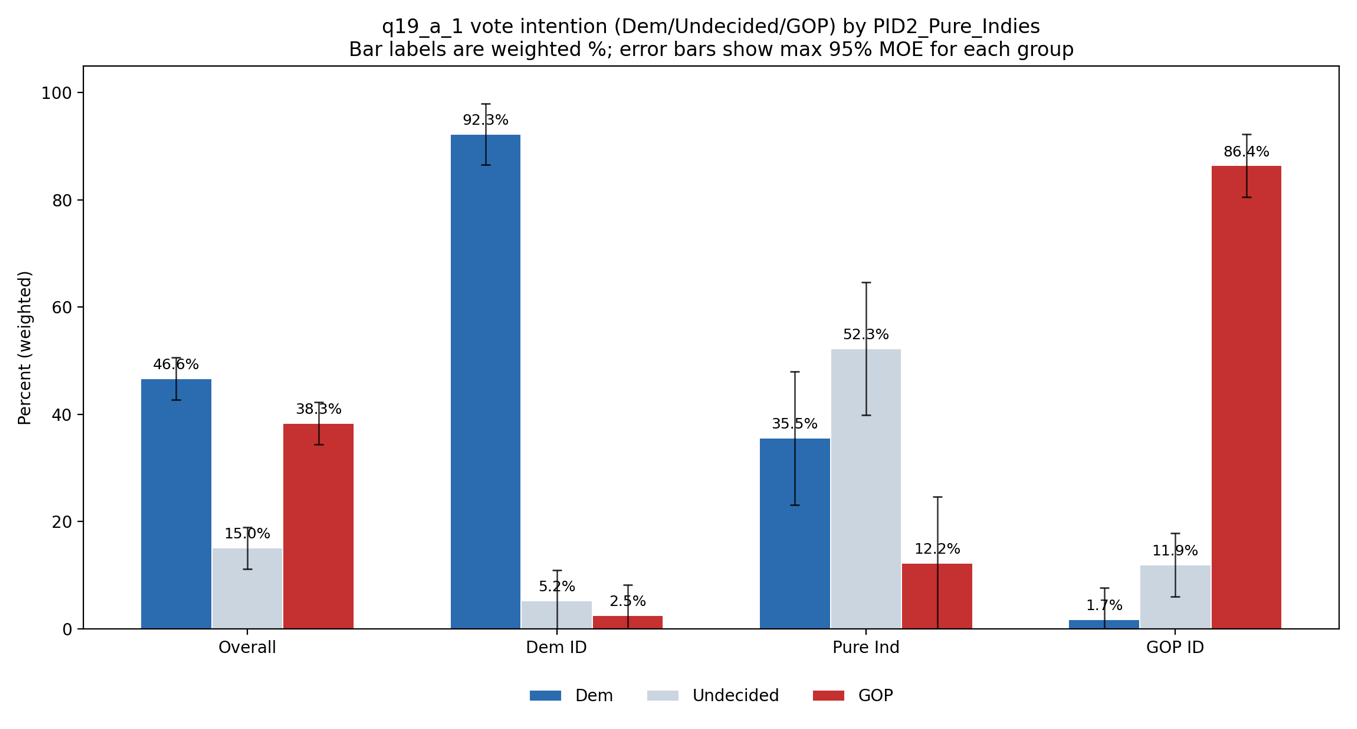

And when analyzing against ‘true partisans’ (including the leaners into their respective camps), we see a different dynamic at work with voter intention on the generic ballot among these pure indies.

While the overall and partisans stay relatively consistent from the initial partisan identification, it’s the ‘pure independents’ who show potential uncertainty, while leaning more Democratic, in their initial vote intentions for U.S. Senate.

Among Democratic identifiers with leaners, preferences are basically locked in. Roughly 92 percent say they’d vote for the Democratic candidate, with only ~5 percent undecided and ~3 percent saying they’d vote Republican. On the other side, Republican identifiers are also unified: about 86 percent say they’d vote Republican, around 12 percent undecided, and only ~2 percent say they’d vote Democratic.

In other words, most of the movement potential isn’t inside the parties; it’s outside them. Partisans are largely settled, including the ‘leaners’ to each party.

That brings us to Pure Independents. This group looks fundamentally different. Only about a third are currently with the Democrat and about 12 percent with the Republican, while a majority say they’re undecided. That’s the biggest takeaway at this point: independents aren’t “swinging” between the two sides so much as they’re still making up their minds at the beginning of 2026.

This is also why independents come with larger uncertainty. Because there are fewer pure independents in the sample, their margin of error is wider (about ±12 points at the 95% confidence level, using the effective sample size from weights). Conversely, the partisan groups have tighter margins of error (about ±6 points). So, the exact independent percentages can move around more from poll to poll, but the broad pattern is hard to miss: partisans are mostly decided; pure independents are, for the most part, undecided in January.

Finally, the differences here aren’t just “noise.” Statistically, the distribution of responses is very clearly different across the three groups (Dem ID vs Pure Ind vs GOP ID). Put simply: these groups are not answering the question in the same way.

Over the next nine months, the Catawba-YouGov Survey will continue testing these ballots, with a focus on two trends. One, will most Democrats and Republicans continue to stick to their ‘home camps’ or are there any defections to the other side? And secondly, how will the election hinge on which way the initial independents break—and where does this large share of them who are undecided decide to move into a partisan camp?

Consistency Across All Contests?

Intentions at the top of the ticket are one thing. Whether those intentions extend down the ballot is another.

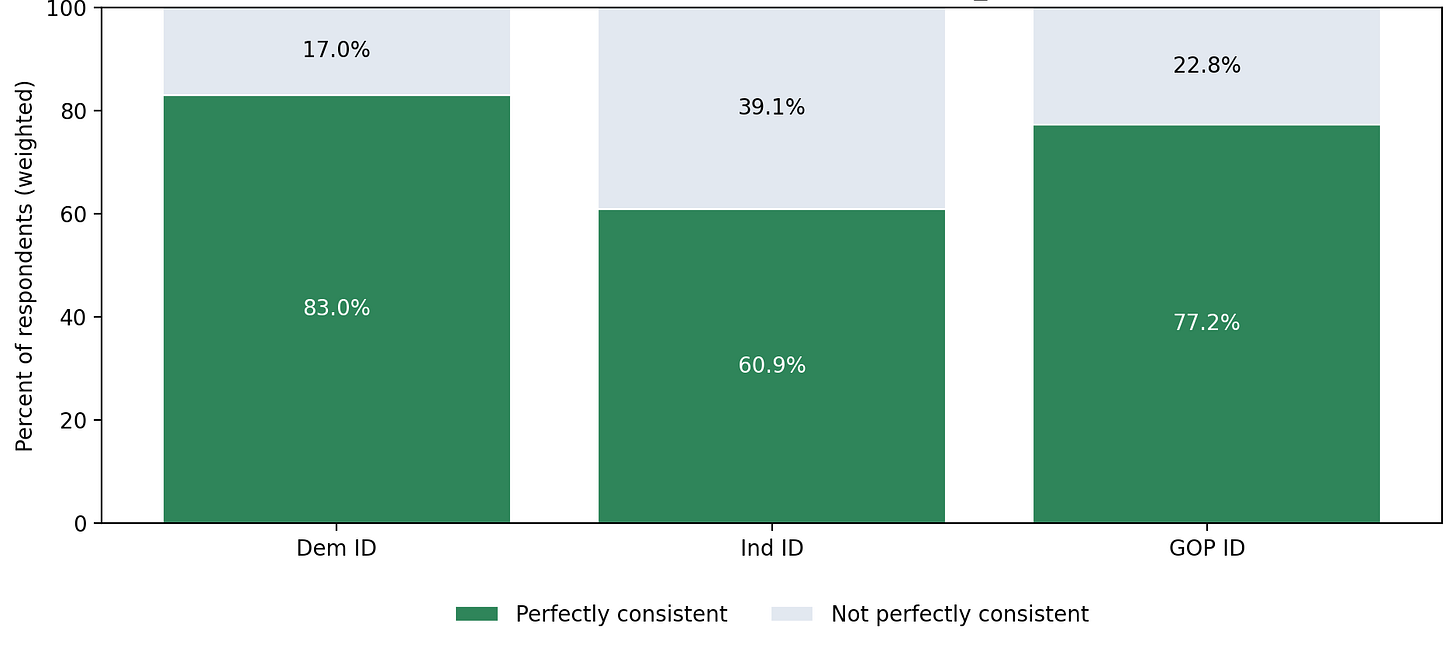

Beyond looking at just the U.S. Senate contest, I looked at how consistent (voting for same party) voters were across the five generic ballot contests. This would give us a sense of how party-loyal North Carolinians may be down the ballot come November.

Again, we see a pretty uniform level of partisan loyalty among the initial partisan identifiers: 83 percent of Democrats and 77 percent of Republicans were ‘perfectly’ consistent—meaning they intend to vote the party across the five contests.

Yet among initial independents, 61 percent were perfectly consistent, leaving about four out of ten independents to ‘bounce down the ballot’ and split their ticket.

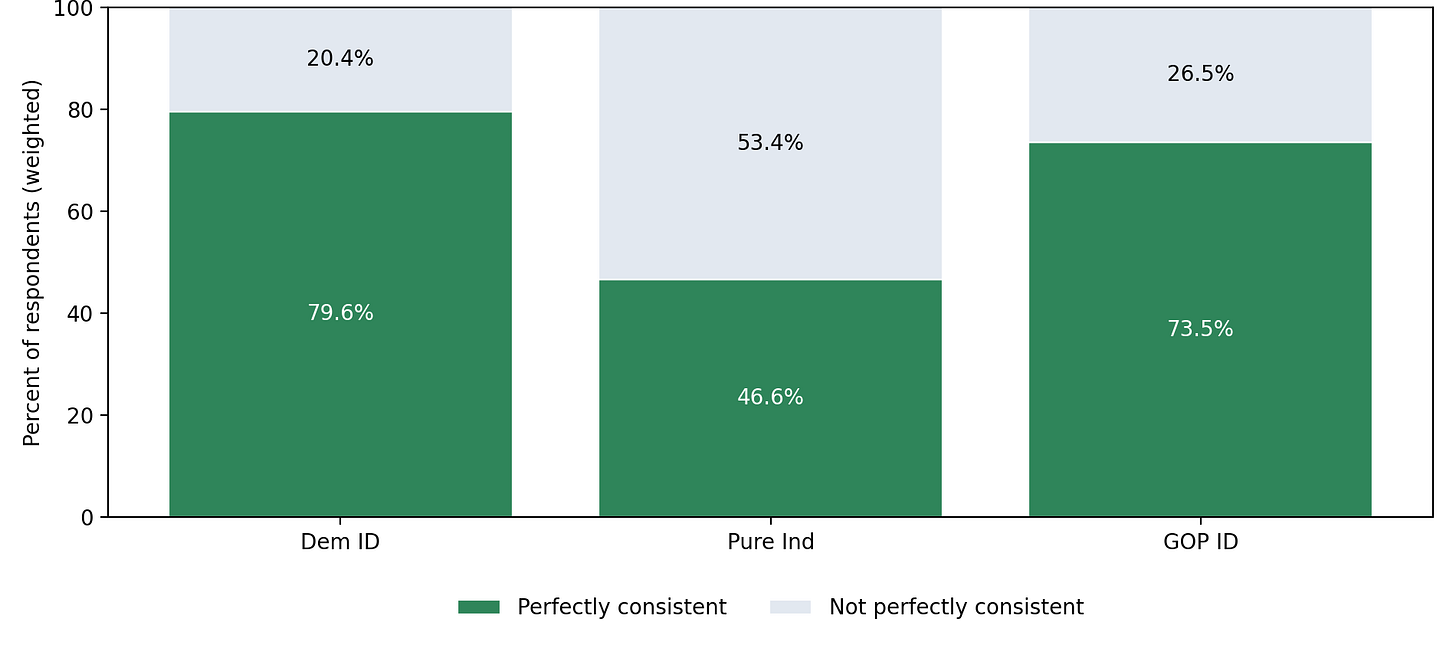

When sorted into clear partisan identifiers (this includes the leaners) against the pure independents, we see the perfect consistency remain high among both partisan groups, while pure independents signal a potential of split intentions down the ballot.

The 9-Month Road from Intention to Decision

What these early results ultimately suggest is less about who is ahead today and more about who is still movable tomorrow. Democratic and Republican identifiers—especially when leaners are included—show a high degree of stability both at the top of the ticket and down the ballot. The real variability lies among pure independents, who are not so much swinging between parties as they are still deciding whether to commit at all.

As the election calendar progresses and nominees become known quantities, the central question won’t simply be whether partisans hold their ground—they likely will—but whether undecided independents consolidate, split, or disengage.

In a closely divided state like North Carolina, the difference between those paths is often what separates a predictable outcome from a surprising one.

Convention wisdom has the U.S. Senate general election between Democrat Roy Cooper and Republican Michael Whatley, but as the voters are making that decision now with early voting leading up to the primary, the generic ballot is best to ask until we know the certified results from March 3.