Having taught two courses this semester, one on State and

Local Politics and the other on Presidential Politics, I came to the end of the

semester with some thoughts that may intersect between the two

topics: one about presidential "cycles," another about the

demographic changes going on in our nation and in the Old North State, and the political polarization that

we continue to experience. Based on a recent guest lecture to a civic group in

Charlotte that brought these thoughts together, I thought I would share these

ideas.

In my remarks, I first gave a sense of what we may be seeing in terms of a "presidential cycle" that could impact our political environment in the not-too-distant future. This cycle may be influenced by my second point, the tectonic shift caused by generational cohorts with very different views. Finally, I ended the talk with a sense of how, even with the possible end of a presidential cycle due to the on-going generational shift, the idea of polarization will like stay with us for some time.

To begin with, I describe the four parts of what Yale political scientist Stephen Skowronek

would say is a presidential cycle, with the New Deal era as an

example and the relationship to today's presidential cycle. The initial/inaugural part of a new presidential cycle, based on the

following attributes, is described as a "reconstructive" president and

the political environment that he enters into:

- The previous ideology and interests have become vulnerable to direct repudiation as failed or irrelevant to the problems of the day

- The new president shatters the politics of the past

- He orchestrates the establishment of a new coalition

- He enshrines their commitments as restoration of original values

- He resets the very terms and conditions of constitutional government

- The reconstructive president brings a new era with a president heralding from the opposition to the previously established era/breaks the old political regime/era

- What these presidents do, and what their predecessors could not do, was to reformulate the nation’s political agenda altogether, to galvanize support for the release of governmental power on new terms, and to move the nation past the old problems, eyeing a different set of possibilities altogether.

- These reconstructive presidents are seen as great party leaders

- Each reconstructive president stood apart from previously established parties and appealed to the interest of budding opposition movement to forge a new movement

FDR can be considered as someone who sought to reinvent the

relationship between government and its citizens in dealing with the Great

Depression, and heralded a new governing coalition under the broad parameters

of the new Democratic Party. This reconstruction of a new presidential cycle

ultimately leads to the creation of a new political dynamic and era in American

politics.

Following the reconstruction of the political environment is a

president who brings about the politics of "articulation":

- These presidents are orthodox-innovators who stand in national politics as ministers to the faithful from the coalition built by the reconstructive president

- They galvanize political action with promises to continue the good work of the past and demonstrate the vitality of the established order in changing times

- Their obligations are to uphold the gospel and deliver the expected services in the prescribed manner

- These “great regime boosters” celebrate received formulas in the exercise of their transformative powers, and prior commitments pressed in on them from all sides

- Their objective is to fit the existing parts of the regime together in a new and more relevant way

- These presidents, however, bring about a debilitating debate over the true meaning of the faith

- Many presidents inherit a political potent agenda but find the exercise of power on its behalf constrained by partisan divisions within the government

- Within these eras of majority-party government, when expansive possibilities for innovation exacerbate disagreements within the establishment and accelerate debates over the true meaning of orthodoxy

- These presidents act on collectively generated premises and pursuing purely constructive visions of change, these presidents rupture the political foundations on which the program and the vision both rest.

In the New Deal presidential cycle, LBJ is identified as the

"articulation" president, who faced not just the apex of the New Deal

majorities, but also began the descent from Democratic dominance in electoral

politics of the nation, due to the divisions within the Democratic Party between

liberals and conservative Southerners, who were realigning into the Republican Party.

Each cycle will usually see presidents from the opposition elected, what Skowronek labels as "preemptive" presidents:

- These presidents are opposition leaders in the reconstructive regimes

- They interrupt a still vital political discourses and try to preempt its agenda by playing upon the political divisions within the establishment that affiliated presidents instinctively seek to assuage

- Their programs are designed to aggravate interest cleavages and factional discontent within the dominant coalition

- However, the political terrain is always treacherous for these opposition presidents

- The hallmark of the opposition leader in a resilient regime is his independence from the stalwart opposition as well as the orthodox establishment

- Always become challenged by majority regime members

Both Eisenhower & Nixon are seen as preemptive presidents

during the New Deal presidential cycle. What's interesting is that Nixon's

presidency (mired in controversy, certainly) appears to herald the next cycle

and the coalition that a reconstructive president will be put together:

starting with fiscal conservatives, Nixon brings in the national security

conservatives brought into the Republican Party by Goldwater in 1964 and

southern Conservatives lead by the Southern Strategy and Strom Thurmond's party

switch.

Finally, the presidential cycle ends with the politics of

"disjunction," based on a president who:

- is affiliated with a set of established commitments that have in course of events been called into question as failed or irrelevant responses to the day’s problems.

- can’t affirm the integrity of government commitments or forthrightly repudiate them

- believes that he and he alone can fix things

- the president's authority to control the political definition of the moment is completely eclipsed

- is consumed by a problem that is really prerequisite to leadership

- President gets submerged in the problems he is addressing

- finds himself an easy caricature of all that has gone wrong

- tends to have only the most tenuous relationships to the establishments they represent

- sever the political moorings of the old regime and cast it adrift without anchor or orientation

- becomes wholly inadequate to sustain the legitimacy of innovation

- leads to crisis of legitimacy nationwide and opens the door to something much more radically different

With his call of

"government is not the solution to our problems, government

is the problem," Reagan brought about a new governing coalition

and philosophy that repudiates the New Deal and brings about the above

reconstructive principles into American politics and government. In addition,

Reagan built on Nixon's electoral foundations with the completion (by at least

1984 and Reagan's re-election bid) of the South and social conservatives,

especially white evangelical Christians.

This coalition becomes the dominant governing coalition and could

be considered at its apex with the articulation presidency of George W. Bush,

especially due to the role of social conservatives and white evangelical

Christians.

The presidencies of Clinton and Obama seem to demonstrate the

qualities of pre-emptive politics, especially with Clinton's triangulation of

centrist politics and policies while acknowledging the "era of big

government is over." For Obama, like with Nixon, the beginnings of a new

reconstructive phase seems to be developing with a critical electoral component

that I'll cover shortly.

The final presidency of a cycle is based on a president who

believes "he, and he alone, can fix the issues" confronting the

nation. President Trump has indicated that he can only fix the situation confronting the nation.

The other aspects of a disjunctive presidency, especially the tenuous

relationship with his own party's establishment, seem very prevalent for what

has been experienced in the first year of the Trump presidency.

So, if one was to draw the New Deal and Reagan presidential cycles out, it might look something like this:

So, if one was to draw the New Deal and Reagan presidential cycles out, it might look something like this:

If the Reagan cycle is coming to an end, it could be due to

the other major stream in our politics and my second key point: the

tectonic shift within our electorate and society based on generations.

As defined by the Pew Research Center, the

shift is coming due to the resulting tectonic plates of Baby Boomers, those

born between 1945 and 1965 and who are currently 54 to 73, and Millennials,

those born between 1981 and what some have defined as 1996 and who are currently

22 to 37 years old.

The Pew Research Center has amassed a significant amount of

research on generations, and here are some examples of what we are seeing with

the Millennial generation--first, the generational impact on the workforce:

In addition, the Manpower Group estimates that by 2020—that’s only 2 years from now—Millennials will make up 35% of the global workforce.

It’s not just in the workforce, but in the U.S. electorate that Millennials are going to have an impact.

In fact, if you combine Millennials with Generation X, the 2016 electorate has already seen the shift away from Baby Boomer dominance. The missing factor is turnout with the Millennial generation.

In North Carolina, one can see this trend mirrored in generational turnout by registered voter cohorts, based on research I have conducted of the past few electorates:

With the 2020 election just around the corner, it is likely that Baby Boomers will have share the same percentage of the eligible electorate as Millennials. But Millennials have taken a significantly different approach to partisan self-identification:

In North Carolina, one can see this trend mirrored in generational turnout by registered voter cohorts, based on research I have conducted of the past few electorates:

With the 2020 election just around the corner, it is likely that Baby Boomers will have share the same percentage of the eligible electorate as Millennials. But Millennials have taken a significantly different approach to partisan self-identification:

For comparison to the other generations:

This trend of political "independence" is evident if you study voter registration in North Carolina. As of May 5, 2018, when the state board of elections released its weekly voter registration figures of the 6.9 million registered voters in North Carolina, with thirty-two percent of the voter pool under the age of 37, a growing plurality of North Carolina's voters are registering as "unaffiliated," thanks to younger voters:

But does this self-identification as "independent" and "unaffiliated" registration really mean that these voters are truly "independent"? Pew provides insight into this aspect of whether these independents "lean" to one party over the other:

When factoring into account the partisan identifiers and the leaners to a party, this means that only sixteen percent of Millennials view themselves as "pure" independents, matching the sixteen percent of Generation X who are pure independents as well.

So, if Millennials are substantially more Democratic in partisan self-identification, how might their voting behavior reflect this? Pew's research on the "young/old" voting gap between 1972 and 2012 gives some insight:

Since 2000 nearly equal match between voters 18-29 and over 65 years old, the gap has been widening, with Millennials coming of voting age eligibility in 1998 and continuing to increase their presence in the electorate.

Another facet that gives some credence to Millennials being more Democratic are their views of both parties:

Half of Millennials have a favorable view of the Democratic Party, with 40 percent having a favorable view of the Republican Party.

Another aspect of the difference among Millennials is their ideological perspective, in comparison to other generations:

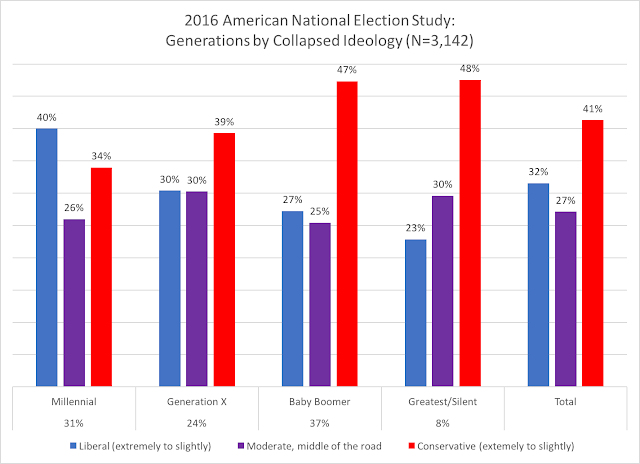

From the 2016's American National Election Study, the ideological composition of the electorate (those respondents who indicated an ideological perspective of liberal, moderate/middle-of-the-road, or conservative) shows differences among generations as well:

Comparing Millennials to the other generations, the liberal plurality within Millennials is striking in contrast to the conservative pluralities in the other generations and the nation as a whole.

In looking at various social issues between the generations, it is obvious that there is a demarcation line between a more liberal-oriented Millennial generation and other cohorts:

Finally, when comparing generations, a noticeable shift occurs with Millennials that may offer the rebuke of Reagan's "government is the problem" belief:

While 59 percent of Boomers believe in Reagan's philosophy of smaller government, a majority of Millennials--53 percent--believe in the idea of bigger government that provides more services.

Taking the above perspectives on Millennials, I believe that it would be easy to see the combination of Millennials coming into their own political right, married with the dynamics of a possible disjunctive presidency, to bring about a new presidential cycle and a reconstructive presidency in the very near future.

However, this doesn't mean that partisan loyalty, or what we might describe as part of the political “polarization,” doesn’t go away with the change in generations or a potential change in the presidential cycle.

If “partisan loyalty” is defined as being the percentage of voting for a party’s presidential candidate, what we have seen over the past three presidential elections is strong loyalty, even among those independents who "lean" to one party, as evident in the past three presidential elections:

As shown in the above three charts, party loyalty is a pronounced factor in presidential vote choice, with pure independents splitting their vote, but typically being 10 percent or less of the electorate. To summarize the 2016 election:

- strong partisans voted 97% of the time vote for their party’s presidential candidate;

- not very strong partisans voted 75% of the time vote for their party’s presidential candidate;

- independent leaners to a party voted 80% of the time vote for their leaned party’s presidential candidate; and,

- pure independents split down the middle.

In looking by generations, one can see the distinctiveness of partisan loyalty as well, based again on American National Election Studies data from 2016 and taking the self-identification partisanship and grouping the strong partisans, not-very-strong, and leaners together:

Baby Boomers, who went 49% Trump to 46% Clinton and were 46% self-identified Democrats, 46% Republican, and 8% pure independent:

Generation Xers in 2016, who voted 51% Clinton to 41% Trump and 8 percent for a 3rd Party candidate and were 50% self-identified Democrats, 40% Republican, and 10% pure independent:

And Millennials in 2016, who went 53% for Clinton to 35% for Trump, with 11% voting 3rd party and were 55% self-identified Democratic, 37% Republican, and 9% pure independent:

So what is my thinking at the end of this semester and blog post? Well, if the Reagan presidential cycle is indeed coming to an end, a new reconstructive presidency may be on the cusp of coming into being if Millennials begin their transformation of the electorate, and the political pendulum swings to the political left. But what appears more evident is the fact that polarizing partisanship will not change anytime soon.

This summer I'm doing a lot of reading on polarization in the United States, with the intent of teaching a special topics course called "Polarization in American Politics" next academic year. Another post will focus on some of the readings that I'm doing, but one that I am particularly struck by so far is James E. Campbell's Polarized: Making Sense of a Divided America. I would highly recommend it, for both the expert and the lay reader.

This summer I'm doing a lot of reading on polarization in the United States, with the intent of teaching a special topics course called "Polarization in American Politics" next academic year. Another post will focus on some of the readings that I'm doing, but one that I am particularly struck by so far is James E. Campbell's Polarized: Making Sense of a Divided America. I would highly recommend it, for both the expert and the lay reader.