By Michael Bitzer

With the data finalized from the 100 counties and available via the NC State Board of Elections, we can now parse through who showed up to vote based on a number of factors. As reported in the Raleigh News and Observer recently, May's primary electorate had only two out of ten NC registered voters participate. But with the counties reporting their voter history data to the NC State Board of Elections and using the May 21 voter registration data file, we can see who showed up for May's primary. This blog post will look a variety of factors, specifically highlighting more detailed information based voter party registration, generational dynamics, and the location and type of precincts voters casting May primary ballots came from.

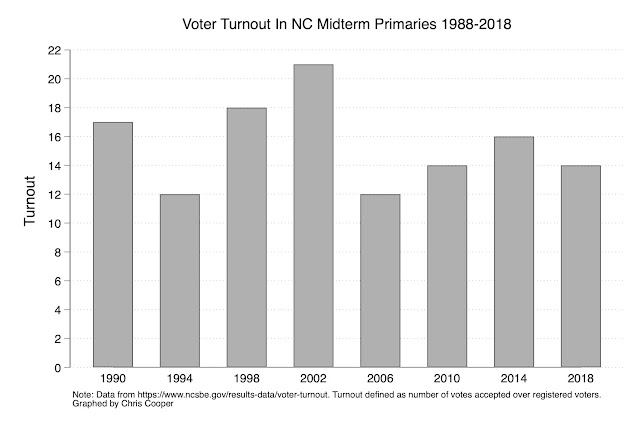

Slightly over 1.4 million registered NC voters cast a May 2022 ballot, amounting to almost 20 percent registered voter turnout. That's the highest turnout in twenty years, as my colleague Chris Cooper noted in a previous blog post and chart:

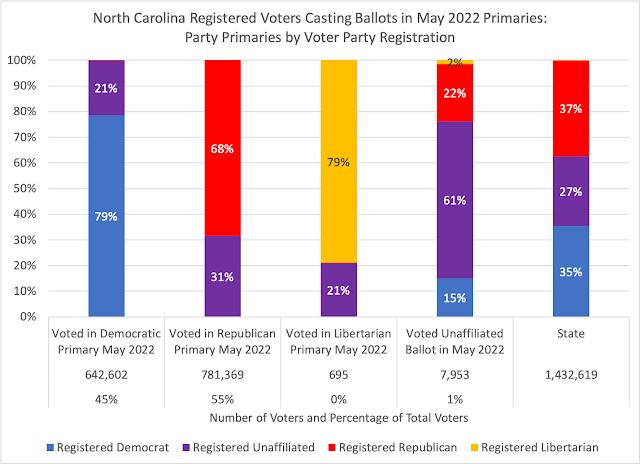

Between the two major parties, Republicans saw over 780,000 ballots cast (55 percent of the total ballots cast) compared to Democrats with over 640,000 ballots (45 percent). This shouldn't be a surprise, given the top-of-the-ballot on the GOP side featured what many thought was a competitive U.S. Senate nomination battle (which turned out it wasn't).

Even with their recent dominance in the voter registration pool, Unaffiliated voters didn't show up at the same turnout levels as partisans: Unaffiliated voters had a 15 percent turnout rate, while Republicans and Democrats had a 24 and 20 percent turnout rate, respectively.

What about these Unaffiliated party primary voters?

One area of interest regarding Unaffiliated voters are those who show up to vote in party primaries and their voting "habit," or behavior, when it comes to pulling a party ballot. With voter history data from the 2018 and 2020 primary elections, we can see the universe of those Unaffiliated voters who voted in all three primary elections and their habits when it comes to voting in the primaries.

First, I constructed a series of classifications for the Unaffiliateds who voted in all three of the past primaries, based their voting habits:

If an Unaffiliated voted in all three Democratic or Republican primaries, then they would appear to be a consistent Democratic or Republican primary voter. A variety of explanations could be explain this behavior, such as whether they are just a "masked partisan" by choosing the Unaffiliated registration but are partisan voters, or whether they live in a solidly partisan area, thus the only real choice is voting in one party's primary over the other.

The second classification could be 'strategic' party voters, meaning they voted in a competitive party primary, such as voting in 2018's "Democratic wave year" and 2020's competitive Democratic presidential primary but then switching to the 2022 Republican primary. The two scenarios listed above (in yellow) would likely explain the best reasons for selecting the party primaries (Democratic strategic party switcher = voting in the 2018 and 2020 Democratic primaries, but switching to the 2022 Republican primary; Republican strategic voter would have voted in the 2018 and 2022 Republican primaries, but then pulled the 2020 Democratic primary ballot with the competitive presidential contest).

A third type of Unaffiliated primary voter could be the party convert, or party switcher: going from one party in 2018 to the other party in 2020 and 2022 might indicate that the voter simply aligned with the new party more so than they did in 2018.

Finally, we have 'floaters,' or perhaps 'party wanderers': a combination of the three party primaries (coding #3 and #7) that really makes no rhyme or reason (especially coding #3), unless there are local conditions or issues at play for that voter.

The key test would be the numbers of Unaffiliated voters falling into each category. In looking at the May 21, 2022 voter registration file, slightly over 120,000 registered Unaffiliateds cast ballots in all three primary elections, and the division broke down into a very distinct portrait of these Unaffiliateds.

Over two-thirds (68 percent) of the 2018 to 2022 Unaffiliated primary voters voted consistently in one party primary over the other (this combines both Democratic and Republican primaries). The remaining Unaffiliated voters were either strategic party voters (a combined 18 percent voted in two of the same party primaries but went to the other party one year for a competitive contest) or were simply party switchers (11 percent who voted in one party in 2018 but then voted twice in the other party in 2020 and 2022). The 'floaters' or party wanderers were less than 3 percent.

More study is needed on North Carolina's Unaffiliated voter pool and their voting habits, but this early analysis could give us a better sense of what kind of voters Unaffiliateds are: if they are showing up consistently for primary elections, then these voters would be seen as some kind of engaged partisans. And if they are consistently voting in the same party, then are they really 'unaffiliated' from partisanship?

Demographics Continue To Show Distinct Partisan Divides

Not surprisingly, May 2022's primary demographics showed real divides within race/ethnicity, gender, generations, and voter locations of those who cast ballots.

In looking at voter race & ethnicity, over two-thirds of White non-Hispanic/Latino voters picked the GOP ballot, while 97 percent of Black/African American non-Hispanic/Latino voters went for the Democratic ballot. Hispanic/Latino (any race) and all other races (non-Hispanic/Latino) voters went 60/40 Democratic, while the "unknowns/unreported" race & ethnicity were evenly split.

While the Republican primary electorate was 94 percent White non-Hispanic/Latino, the Democratic primary electorate was 53 percent White and 39 percent Black/African. Overall, three-quarters of the total primary electorate was White non-Hispanic/Latino, with 18 percent Black/African American and only 1 percent Hispanic/Latino.

Women were evenly divided between the two primaries, while men went overwhelmingly for the Republican primary ballot (61 percent). However, more women showed up in total (55 percent) to men (45 percent).

Generationally, the primary electorate was overwhelmingly old: the average age for both party primaries was 60 years old, fueled by Boomers making up nearly half of the total primary electorate. Combined with the Silent generation, voters over the age of 58 made up 62 percent of May's total primary voters.

In looking at each generation cohort and which party they voted in, there's again a distinct young versus older divide. Voters over 42 went overwhelmingly Republican (Gen X, Boomer, and Silent), while Millennials bucked the trend and went more Democratic in their primary ballots and the youngest generation (Gen Z) evenly split between the two parties.

Regionalism and Precinct Type Reflect Partisan Differences As Well

Finally, where the parties pulled their primary electorates from demonstrates some interesting patterns. First, in looking at North Carolina's 'regionalism' (urban central cities, urban suburbs, surrounding suburban counties, and rural counties), the composition of both party's primary electorates and where each region went for both parties shows distinct divisions.

Among both the Democratic and Republican primary electorate, the base of both parties was well represented. Urban central city voters (who went 70 percent for Biden in 2020) made up a plurality of the Democratic party primary, while surrounding suburban county voters (who went 64 percent for Trump) made up a plurality of the GOP party primary.

When looking at each region, again you see the distinctiveness of which party dominated in those four areas.

Not surprisingly, the most Republican regions were the surrounding suburban counties and rural counties, with the central cities being overwhelmingly Democratic. The most competitive region of the state--the urban suburbs--was slightly more Republican that the state as a whole.

One final 'location' analysis that has become of interest to me is the type of precinct that both parties pulled from for their primary electorates: namely, how polarized or competitive are the precincts where voters reside, and where did both parties garner their votes from among these competitive to polarized precincts.

In determining whether a precinct is 'competitive' or 'polarized,' I categorized each precinct as to the percentage for either Biden or Trump in three categories: 50-54 percent (competitive but lean to one party), 55-59 percent 'likely' for one party, or 60 percent and greater, a polarized precinct for one party.

For the Democratic primary, its voters were fairly distributed: a plurality came from those precincts that went for Biden in 2020 at 60 percent or greater, but the next largest were precincts that Trump won with 60 percent or more of the vote.

In comparison, Republican primary voters came heavily from Trump-dominated precincts, for both registered Republicans and registered Unaffiliateds casting ballots:

Two-thirds of registered Republicans, and over 60 percent of registered Unaffiliateds voting in the GOP primary, were in precincts that went overwhelmingly for Trump in 2020's presidential election, perhaps signaling that the Trump dominance of the GOP is very evident in the party's base of voters.

Primary elections tell us something about the voters and the state of our political parties respectively: when we talk about the 'party bases,' those who take the time to show up to vote in a primary election are likely the most committed to those parties or most energized in being a voter. Primary elections also can tell us demographically what the party's 'base' of voters says about that party. Both North Carolina parties continue to show distinctiveness in their party bases, and this sorting of different bases will likely continue for some time to come.

--------------------

Dr. Michael Bitzer holds the Leonard Chair of Political Science and is a professor of politics and history at Catawba College. He recently authored the book Redistricting and Gerrymandering in North Carolina: Battle Lines in the Tar Heel State, and tweets at @BowTiePolitics.