By Michael Bitzer

With North Carolina having sent out its absentee by mail ballots (and the first ballots in the nation submitted the next day), we start the final leg of this mid-term election, culminating on November 8, 2022 and the county, and then state, certification of the official results for this mid-term election.

Along with my other colleagues, we will have a series of analyses regarding the major contests coming up for the Old North State to decide this fall: from the US Senate and US House contests, to the state legislative and supreme court races. In each, we hope to give some analysis of where things stand in terms of the voter pool, what we have seen in the past in various contests in terms of electoral turnout dynamics, and how this mid-term election may be shaping up.

In this piece, I'll take a look at the overall potential electorate--the registered voter pool as of September 6, 2022--and how it might shape the state-wide dynamics, especially the U.S. Senate contest that has stabilized into one of the most competitive contests, but up to this point seemingly a second-tier battle by the national media.

NC Enters 2022's Election with 7.3 Million Potential Voters

With the campaign's 'unofficial' start of Labor Day, the NC State Board of Elections released its weekly update of the voter registration pool on September 6. The potential electorate of 7.3 million registered voters (those active, inactive, and temporary status) has numerous characteristics that may shape November's election.

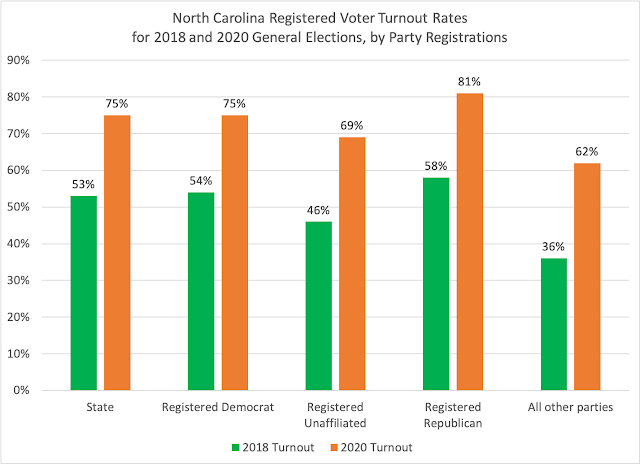

First, a word about turnout, because that will be the standard mantra between now and November ('who shows up' as it is for all elections). As is always the case, presidential year elections have the highest turnout rates, followed by mid-term rates at a reduced level (let's not mention what abysmal rates local, odd-year elections tend to have).

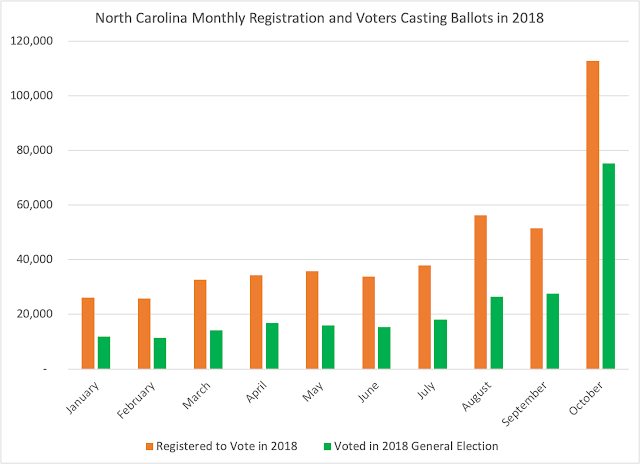

In North Carolina, the past few mid-term elections have seen a pretty consistent turnout rate, but 2018 broke that trend, as evident in this chart:

Since the 1966 mid-term election, North Carolina has averaged 47 percent turnout of its registered voters, with a low of 36.6 percent in 2006 to a high in the most recent mid-term in 2018 of 53 percent.

One important note about the 2006 and 2018 mid-terms: they were 'blue-moon' election cycles, with no U.S. Senate race to capture state-wide attention. Considering also that 2020's presidential election had 5.5 million, or a 75 percent turnout rate and the highest since 1968, we are potentially witnessing an elevated turnout trend beginning in the state.

Other reasons for the elevated turnout could be the sheer competitiveness that North Carolina has seen in its electoral dynamics since 2008, with typical margins of victories for state-wide offices at five percent or less. Another potential factor is that the state's political divisions have deepened over the course of polarization, thus engaging voters to participate.

When it comes to November 2022's turnout rate, I think a safe bet would be to take the average of 47 percent, and with 7.3 million voters, we could see close to 3.5 million cast ballots this fall. But with the recent dynamics at play, we may see that number higher. If 2018 is a 'new day' in turnout, just a boast of six percentage points above the average could see closer to 3.9 million North Carolinians voting come November.

If 2022 sees an increase beyond 2018's turnout rate, then 4 million-plus voters could set a whole new dynamic for the state's electorate. But more on that aspect later in the post.

So Who Are These 7.3 Million NC Voters?

In forthcoming posts, we'll provide spreadsheets with relevant voter registration and past turnout dynamics for each current congressional and legislative contests. With the US Senate as a state-wide contest, we'll look broadly at the pool to see who these voters are and how many showed up in the past two elections.

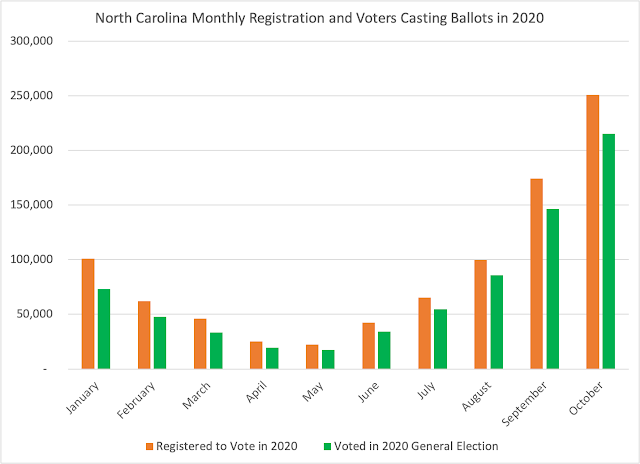

It is important, however, to note that the 'pool' is not set in stone as of yet: September and October tend to be the two most active months for registration, especially with 'same-day registration' during early voting in October. From 2018's and 2020's monthly data, we see that as the election draws nearer, the numbers increase, along with the likelihood of those newly registered voters actually casting a ballot.

So, with the expectation of having this month and October (especially with its same-day registration and voting), we will add more North Carolinians to the rolls and ballots before Election Day (a reminder: the official deadline for registering for the election is October 14, but if you miss that, you can register and cast a ballot at the same time during early voting).

With this voter registration data, we can break down the 7.3 million North Carolinians via party registration, race & ethnicity, gender, generations, and regional location, using the Sept. 6 voter registration data file.

First, by race & ethnicity, NC's voter pool continues to diversify.

White non-Hispanic/Latino voters continue to see its percentage decline, down to 64 percent. 2018's election saw Whites at 68 percent, while in 2020, it was 66 percent. Black/African Americans are holding steady at their twenty percent, while Hispanic/Latinos have increased slightly from 3 to 4 percent. The largest increase has been the "unknown/unreported," and that trend has been a growing one where registering voters simply don't 'check' a box to indicate their race or ethnicity when they register. Four years ago, less than 4 percent of NC's voters indicated no race or ethnicity.

The party registration status of each racial/ethnic group continues to show the influence of the unaffiliated voter. Among White voters, unaffiliated has gone from 34 to 37 percent, with Republicans holding steady at 41 percent and Democrats dropping from 24.5 to 21 percent. Among Black/African American registered voters, unaffiliated registrations have gone up from 17 to 21 percent, while among Hispanic/Latinos, a slight increase from 42 to 44 percent.

Much has been made this year regarding gender dynamics, and while NC has not experienced the same shift of women registering to vote as in other states, the 'gender gap' as studied by political scientists is apparent in party registration.

Since 2018's mid-term, both genders have become more unaffiliated, with both becoming slightly less Democratic (both saw drops of three percentage points from 2018), while Republican percentages held steady.

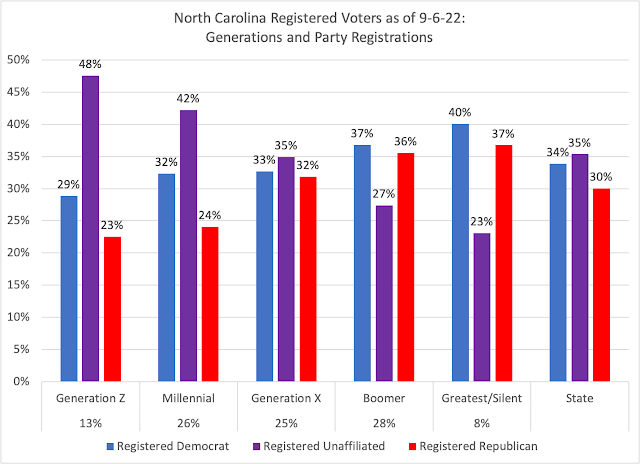

Another distinctive pattern in North Carolina is the generational dynamic. As with the nation, the Old North State is undergoing significant generational replacement, especially when viewed through cohorts.

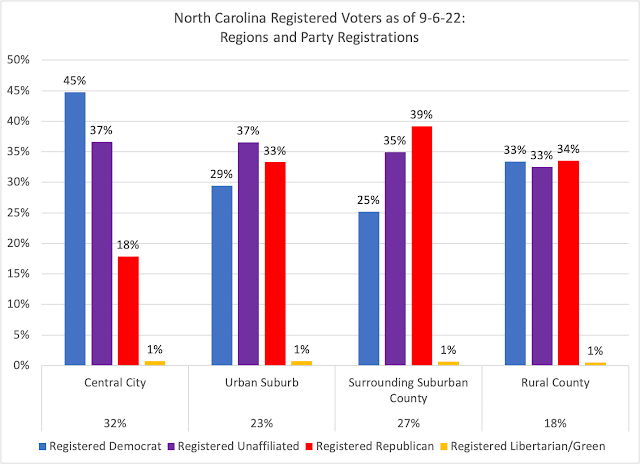

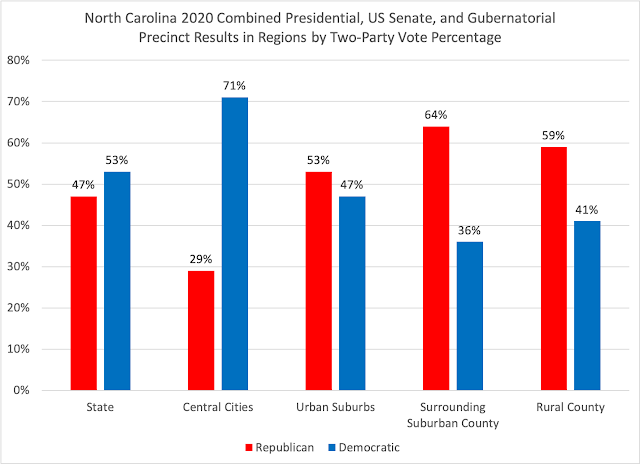

And in breaking up where each party registration resides, half of each party's voters reside in precincts that are overwhelmingly partisan to that party. Conversely, unaffiliated voters mirror the state-wide's U-shaped distribution.

So when registered partisans met someone who lives in an opposite-polarized precinct and think "my heavens, what is wrong with that person? Everyone I live around votes and thinks like me!", then you can understand how the North Carolinians have 'sorted' themselves into like-minded communities.

Finally, to return to the introductory point of this post, with unaffiliated voters commanding a plurality of registered voters, driven in large part to those under-40 year olds, it is still important to remember the mantra "who shows up" when it comes to the actual electorate.

The stark difference between Millennials and Generation Z, as compared to Boomers, is significant in the past two elections. If Millennials and GenZ show up comparable to the state's overall turnout rate (thus making up double-digit deficits) this year, a potential tectonic shift could occur in the state's politics.

So How Might All This Impact the Budd-Beasley U.S. Senate Contest?

For several elections now, North Carolina has been home to one of the nation's most competitive, and expensive, U.S. Senate contests. But this year's Beasley-Budd contest, when compared to other US Senate races in Georgia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio for example, seems to be the 'sleeper' race, alongside Florida's contest, when it comes to national attention.

Without anything else to go on but the latest polling and the fact that Beasley has pretty much been on TV all summer, while Budd has begun his advertising now following a quiet summer, it does seem that the race is that close. It’s probably a 'within the margin of error' race at this point, when Budd should have a clear lead, but it feels like something else going on that makes this an 'odd' environment compared to what we should be expecting.

Normally, congressional mid-terms are considered referendum's on the president's party, and when the president's party holds unified government, the likelihood is that (with only two exceptions), the majority party will suffer at the polls and lead us to divided government.

Much of what political scientists know is that there are certain 'fundamentals' when it comes to mid-terms to evaluate: the president's approval rating, the number of competitive districts (especially post-redistricting activities), economic dynamics, and partisan voter behavior.

But as we begin the last leg of 2022's campaign, an odd dynamic is at work: first, the 'generic congressional ballot,' meant to indicate which party voters will cast their ballots for, regardless of named candidates, is now tied between the two parties. In a 'normal' environment, Republicans should see a distinct advantage on this measurement, and perhaps it will happen as we count down to November.

The other aspect 'at-odds' with the normal fundamentals: Biden's approval ratings. Still in classic 'danger' territory, there has been a noticeable uptick in his approval ratings, per Real Clear Politics average. It's likely that Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, while not happy with the president's performance, are 'coming home' to support their party, or more likely, to vote against Republicans, the prime effect of negative partisanship.

Much of this is national dynamics, things out of control of both Budd and Beasley as they prepare for the ballots to be cast. In addition, the general energy that the Dobbs abortion decision may have made in the Democratic base, along with the FBI search and Trump’s retorts to it and any future events (the return of the January 6th investigation committee's work, for example), could further shape the electorate's thinking.

Of course, everything could revert back to the standard dynamic of an inherent GOP-advantage between now and November. But with 2018 and 2020 seeing such high levels of turnout, North Carolina may be in a ‘new normal’ of polarized elections sparking increased turnout among all groups. And with this kind of competitive race truly playing itself out, and some other factors—generational replacement, the role of the unaffiliated voter—then all bets may be questionable in terms of where things go towards November.

With the final stretch upon us, I’d watch to see what new polls have to report, but if it’s a constant tie moving forward, then I’d think some major money would start to get dump into this state for advertising, beyond what the Senate Leadership Fund has allocated. Money could be a determinative factor, especially in fueling the 'air war' of advertising, and a burning question for the Beasley campaign is, when do D.C. Democrats start pouring in real money into this state on her behalf?

It feels like they are waiting for something to turn the spigot on, but the polls and Beasley’s continued good fundraising numbers would seem to be that needed "twist." Or, with several key races needing defending to just hold 50 seats, maybe DC folks got burned with Cal Cunningham's late-race debacle in 2020, and thus are saving their resources for needed defenses elsewhere.

On the Republican side, it does feel like the Budd strategy is to simply grind it out, hoping the election's fundamentals work out to his favor. But that may be an overly cautious strategy in this post-Dobbs, Kansas abortion amendment, and special election results environment for a state where the margin of victory could yet again be razor thin.

In other words, buckle up North Carolina: it's likely to yet again be another bumpy ride to November 8th.

--------------------

Dr. Michael Bitzer holds the Leonard Chair of Political Science at Catawba College, where he is a professor of politics and history. He tweets at @BowTiePolitics.