by Christopher Cooper and Michael Bitzer

Like a dinner guest that just won't leave, we're not done with the 2022 primaries yet. As the inimitable Gerry Cohen shows in the map below, 15 counties have either second primaries (partisan elections where the top vote-getter didn't get above 30% of the vote), runoffs* (nonpartisan elections where the top vote-getter didn't get above a threshold amount of vote), or local elections to look forward to on July 26. Now that the list of July election is set, we thought it would be a good time to review what we know about runoffs and second primaries in North Carolina.

Source: Gerry Cohen's indispensable twitter feed: https://twitter.com/gercohen/status/1532863664377716737?s=20&t=6q8diY2lDR5iqrGOdOJhngA Brief History of Second Primary Rules in North Carolina

Party runoffs, like RC Cola and preternatural obsession with college football, are mostly a southern phenomenon. In 40 states, the candidate who gets the most votes from each party's primary gets the nomination, no matter the winner's ultimate percentage of the vote. In 10 states (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Texas), the top vote-getter must the most votes *and* get pass a threshold percentage of the vote. In eight of those states, the "threshold percentage" is 50 percent. Get a majority and avoid a runoff; fail to obtain a majority and the top two vote getters duke it out in a runoff election. In South Dakota, the threshold percentage is 35 percent, but only applies to Governor, U.S. Senator or U.S. House of Representatives.

Then there's North Carolina.

From 1915 to 1989, the threshold a candidate needed to receive to avoid a runoff in North Carolina stood at 50 percent, just like the rest of the South. Beginning in the 1970s and picking up steam in the late 1980s, however, there was a movement to eliminate the runoff altogether. The call for elimination came was frequently heard from African American legislators who argued that the runoff rule was rooted in racism and disadvantaged black candidates. Not all who advocated for its elimination were African American legislators, however. Republican Senator Jim Johnson made a quintessentially North Carolina argument for eliminating the second primary. "North Carolina should be the number one state for doing away with second primaries because of its great philosophy with regard to basketball. We say, if you get one more point than the other guy, you've won."

In 1989, the NCGA opted not to eliminate the second primary, but rather to lower the threshold needed to avoid a second primary to 40 percent. In 2017 the NCGA lowered the threshold again, this time to 30 percent, where it has stood ever since.

How Many for July's Second Primary?

There are six runoffs and two second primaries scheduled for July 26, 2022, along with several municipal elections. While most of the July runoff elections fall under the 30 percent threshold rule, one (Jackson County Board of Education District 2) still operates under the old 50% threshold, thanks to a still operative local bill passed in 1991.

To learn a bit more about how this year compares to previous runoffs, we catalogued every runoff and second primary from 2010 to 2020 (a harder task than you might imagine) and found that 2022 will have the largest number of runoffs and second primaries since the threshold was reduced from 40% to 30%. In 2020 and 2018 were only 2. 2016 was largely runoff and second primary free (just 1), but 2014, 2012 and 2010 witnessed 17, 22, and 20 runoffs and second primaries, respectively.

What Turnout Might We Expect in July?

Not surprisingly, fewer people vote in runoffs and second primaries than vote in the initial election. But how much lower?

From 2010 to 2020, the average runoff or second primary garnered 40 percent of the voter turnout of the first primary, although there's a wide range of turnout rates, as you can see from the histogram below.

From 2010 to 2020, the race with the highest percentage turnout (compared to the first primary) was 2010's Bladen County Sheriff's Democratic second primary, with 99 percent of the votes cast in the first primary. The lowest was 2012's Democratic second primary for NC Commissioner of Labor, which had 7.5 percent of the first primary ballots cast.

On average, local elections saw 42 percent of the first primary turnout, state legislative races at 41 percent, and federal contests was 38 percent, but state-wide second primaries had only 17 percent first-to-second primary average turnout rates (granted, there were only five contests for statewide office from 2010 to 2020).

How Often Do We Get Different Winners?

The runoff system is based on the idea that the voters might select a different candidate if the choices were more limited, but from 2010-2020, two-thirds of the first primary winners went on to win the second primary.

Of course, that leaves one-third of the contests with a different result between the two primary contests. These include some consequential examples. In the 2020 Republican primary for the 11th Congressional District, Madison Cawthorn, placed second to Lynda Bennett in the first primary, but called for a second primary when Bennett failed to achieve the 30% threshold. Cawthorn subsequently went on to defeat Bennett in the second primary to become the Republican nominee and eventual (one-term) U.S. representative. In the 2014 Republican congressional district 6 primary, Phil Berger, Jr received more votes than Mark Walker, but did not break the 40% threshold. Walker won 60% to 40% in the second primary and went on to serve three terms in Congress.

If we didn't have second primaries, Madison Cawthorn would not have been in Congress, and Phil Berger Jr would likely not be on the NC Supreme Court. How's that for consequential?

Would Voters Want a Different Voting Choice?

Runoffs are not universally loved. Some critics point to the cost of administering another election. Others cite the effects on voter confusion and fatigue. Others still cite the abysmally low turnout in second primaries as a sign that we should rethink the current system.

One alternative election system is ranked choice/instant-runoff voting (sometimes referred to as IVR). Ranked choice voting differs from the plurality/threshold election system where one person is a "winner take all" if they get one more vote than the person who came in second

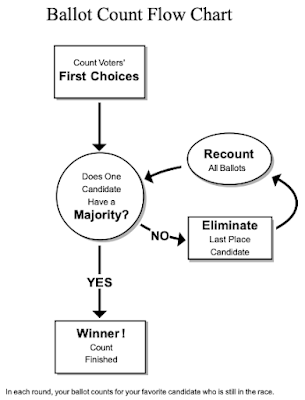

Once all the ballots are cast, the first choice votes are tabulated: if no candidate receives a majority of votes, the process drops the candidate who had the fewest first choice votes. Those voters who voted for the eliminated candidate will have their second choice candidate votes tabulated, and the process continues (lowest candidate eliminated, votes continue through the preferences) until a candidate gets a majority of the votes. Visually, the process looks like this:

Proponents point to two advantages: majority voting and expressed voter choice. In a ranked choice system, the first benefit is that the ultimate winner has to receive a majority of the votes and not a 'threshold' below a majority (for example, North Carolina's 30 to 40 percent to avoid a second runoff primary). Therefore, the ultimate winner can claim that a majority of voters voted *for them* as opposed to up to 70 percent of the voters *didn't* vote for the ultimate winner.

We are not proposing RCV (or any reform) for North Carolina's runoff system, but instead simply offering a reminder that it doesn't have to be this way. The North Carolina General Assembly created our runoff system and tweaked it over the years. They could do so again.

* although runoffs describe non-partisan elections and second primaries describe partisan elections, we use the terms interchangeably throughout the piece.

_________________

Dr. Chris Cooper is the Madison Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Public Affairs at Western Carolina University; he tweets at @chriscooperwcu.

Dr. Michael Bitzer hold the Leonard Chair of Political Science and is a professor of politics and history at Catawba College; he tweets at @BowTiePolitics.